ACTIVITIES & TUTORIALS

A Little Research Project As A Learning Experience: How Can We Define The Smallest Book In The World?

How can we define the smallest book? Would it be by size of the binding, the type font used, metal type, or electronic clicks? I began to answer my question by looking at some notes in various reference books. I also viewed photos of the books. As I reviewed some of the published research and documentation on the books that were part of my question, I encountered the term "smallest book" more than once.

What is the smallest book in the world? I set about to see what could be documented and put into a reasonable format for discussion. As is the story with everything associated with valid research, one always needs a certain amount of qualifiers associated with the question to obtain a reasonably good and defendable answer. Additionally, with the ease of access to online data bases and libraries there is no lack of information that one can discover and then add to original qualifiers while doing the research. As the list of qualifiers deepens so does the number of “books” that might hold the “smallest book” honor.

Doris Welsh, that grand lady of the miniature book world, did a tremendous amount of research about the history of miniature books. Welsh was certainly well prepared to write such a history because her professional life was dedicated to gathering and presenting information about books. Additionally, she published 15 miniature books of her own under the press name of Le Petit Oiseau. She had dedicated almost 25 years to gathering information on the history of miniature books, when unfortunately, she suffered a stroke.

That was in 1965 and Welsh never recovered enough to complete her work. However, with the help of Kathryn I. Rickard, the history was completed and published in 1986. One part of The History of Miniature Books includes a section about the "smallest book in the world." It appears that bibliophiles have been asking the question for years.

Welsh wrote, “What is the smallest printed book in the world? The question seems to have interested collectors of miniature books, collectors, and non-collectors of books in general alike for many years. In 1876-1877, the English periodical, Notes and Queries, published a series of answers to this question. The suggested candidates for this honor ranged from The Rosebud of 3" x 2” to the Bijou Almanack of 1839 of 1/4" x 1/2"."

As I mentioned earlier, there are many ways to answers the question. The very first qualifier to be defined is "What is a book?" Is it something of so many words or pages, or copies, or even digital images? The Oxford Dictionary loosely defines a book as "written or printed pages glued or sewn together along one side and bound in covers." It's a good start but not exactly 100% inclusive, as that would exclude digital copies that are stored on electronic media, objects that are not sewn, and one-page items, etc.

The next twist to find the answer is "Should the book be printed with moveable type or can we include printed images that have been photographically reduced or even printed with some special high-tech software?" This part of the question should also address "printing plates" that are neither moveable nor reduced by some photographic process but are produced by special graphic software. How does one classify a book that may have been produced using the smallest moveable type versus a book printed with a larger type but on smaller pages of paper. Which is the smaller of the books?

As you can see, these queries only scratch the surface of what might qualify a book when speaking about what might be the smallest book in the world. Doris Welsh, in her History published a list of the smallest books printed in each of the last six centuries [15th – 20th]. Her list only goes through to 1964, the date limit of her research and records. During the last half of the 20th century several additional small books have been produced, some in the new electronic format.

1975, Gleniffer Press, Scotland, 3 Point Gill Titling Catalogue, 2.9 x 2.9 mm, letterpress printed, perfect bound

1979, Gleniffer Press, Scotland, Three Blind Mice, 2.1 x 2.1 mm, letterpress printed, perfect bound

1985, Gleniffer Press, Scotland, Old King Cole,, 1.0 x 1.0 mm, lithographic printed, perfect bound

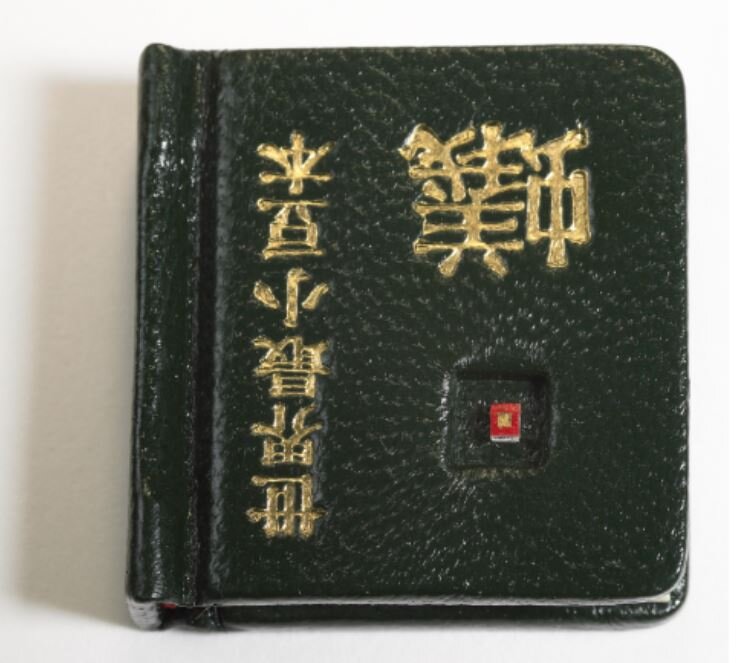

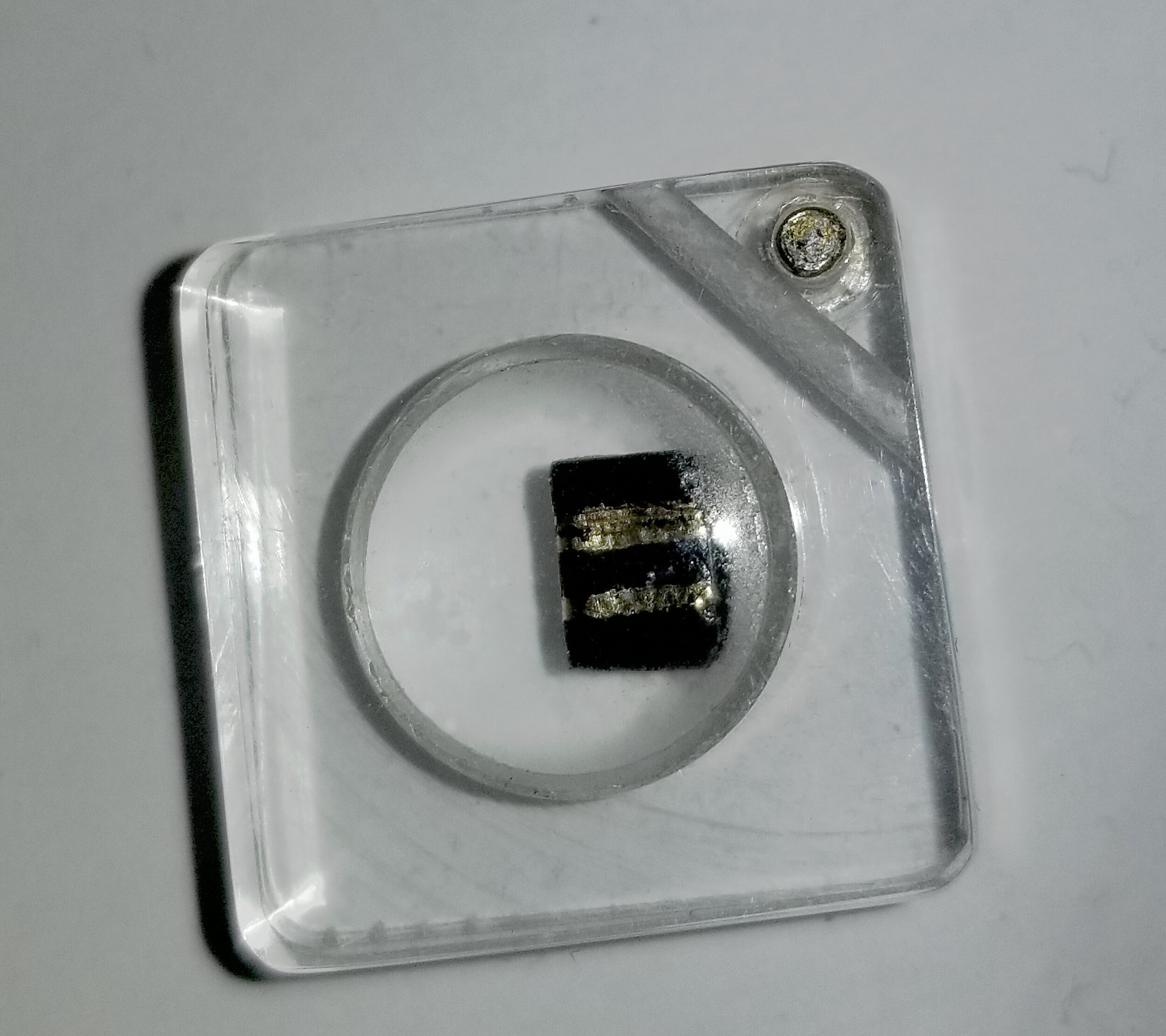

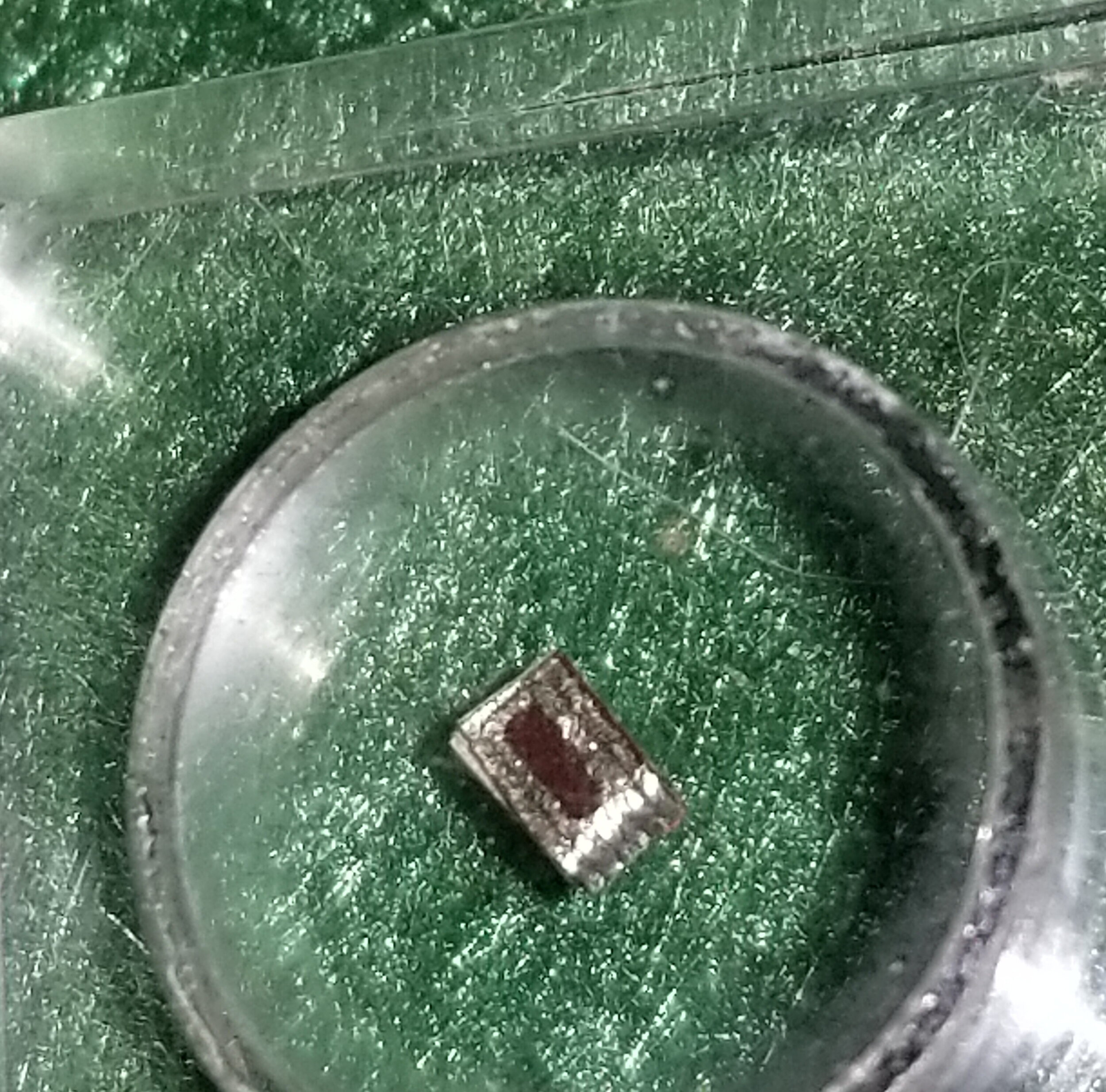

2012, Nano Imaging Facility, Canada, Teeny Ted from Tunip Town, 70 x 100 micros, (.07 x .10 mm), (electron microscope needed for reading)

2013 Toppan Press, Japan, Shiki no Kusabana, .75 x .75 mm, (electron microscope needed for reading)

2016, Institute of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics, Russia, ‘The Steel Flea’, 70 x 90 microns, (.07 x .09 mm), (electron microscope needed for reading)

One can debate the question in one’s own mind or share your thoughts with other bibliophiles. Which processes looking at both the traditional printing as well as the electronic publications should be considered? One might also consider Galileo printed by the Salmin brothers who created the "2 pt. fly’s eye" type. There is also Ian Macdonald’s work Three Blind Mice that is almost 10 times smaller than Galileo. What would Doris Welsh have to say about this today, almost 75 years after she taught herself to set type and run a printing press in the library of the Newberry Library in Chicago?